Pharyngeal spasm

Definition - Pharyngeal spasm

The term “pharyngeal spasm” is an abbreviation of the term “pharyngeal constrictor muscle spasm” used in the original English publications that wrote of the injection of Botulinum Toxin A for the treatment of this problem (see literature). The term pharyngeal spasm has become widespread in international literature; thats why it is used here even though it is not really precise and is somewhat misleading. It is imprecise because it does not affect the whole pharynx. It is misleading because it is not strictly speaking a spasm (cramp), but the retained physiological, circulatory contractibility of a part of the pharynx.

Symptoms

Patients with pharyngeal spasm are usually diagnosed because they are unable to speak even though a voice prosthesis was inserted after their laryngectomy. The voice prosthesis may flow well and be in the correct position, the pharynx wide and open, but the patient is unable to speak despite the greatest efforts to do so. In some cases a very short sound may be produced, which is then quickly blocked.

Pathophysiology

A pharyngeal spasm occurs if no myotomy of the constrictor pharyngis muscle is made during the course of the laryngectomy, and no neurectomy of the pharyngeal plexus, or if they are functually ineffective. The air that is needed for speaking is diverted through the voice prosthesis into the esophagus and prevented by a strong circulatory contraction of the constrictor pharyngis muscle (muscles of the pharynx) from flowing into the mouth. In laryngectomees this process is called a pharyngeal spasm, and it was originally a physiological reflex that prevented food from flowing back from the food pipe into the pharynx and mouth. It needs to be deactivated for TE-speech to be possible, i.e. by myotomy.

NOTE: In the early days of speech therapy using voice prostheses, an insufflation test was usually carried out before secondary voice prosthesis insertion in order to rule out pharyngeal spasm. Insufflation test

Diagnosis

The clinical examination

If pharyngeal spasm is suspected, then the first step is to rule out any problems with the prosthesis or shunt. A transprosthetic endoscopy will establish whether the voice prosthesis is positioned correctly in the shunt and the shunt continuous in the food pipe, and rule out any high-grade stenosis of the pharynx. Furthermore, checks are to be carried out to establish whether the patient can talk if the doctor/SLP closes the tracheostoma without applying pressure to it. A tracheostoma valve may be used for this purpose. It must also be ascertained that the patient is not compromising the PE segment by pressing on the tracheostoma for digital occlusion. This is often the cause of an inability to speak, and can be confused with pharyngeal spasm. If the patient is still unable to speak with unpressured occlusion of the tracheostoma, then it is possible that there is indeed a pharyngeal spasm.

Radiological presentation of the spastic pharyngeal segment

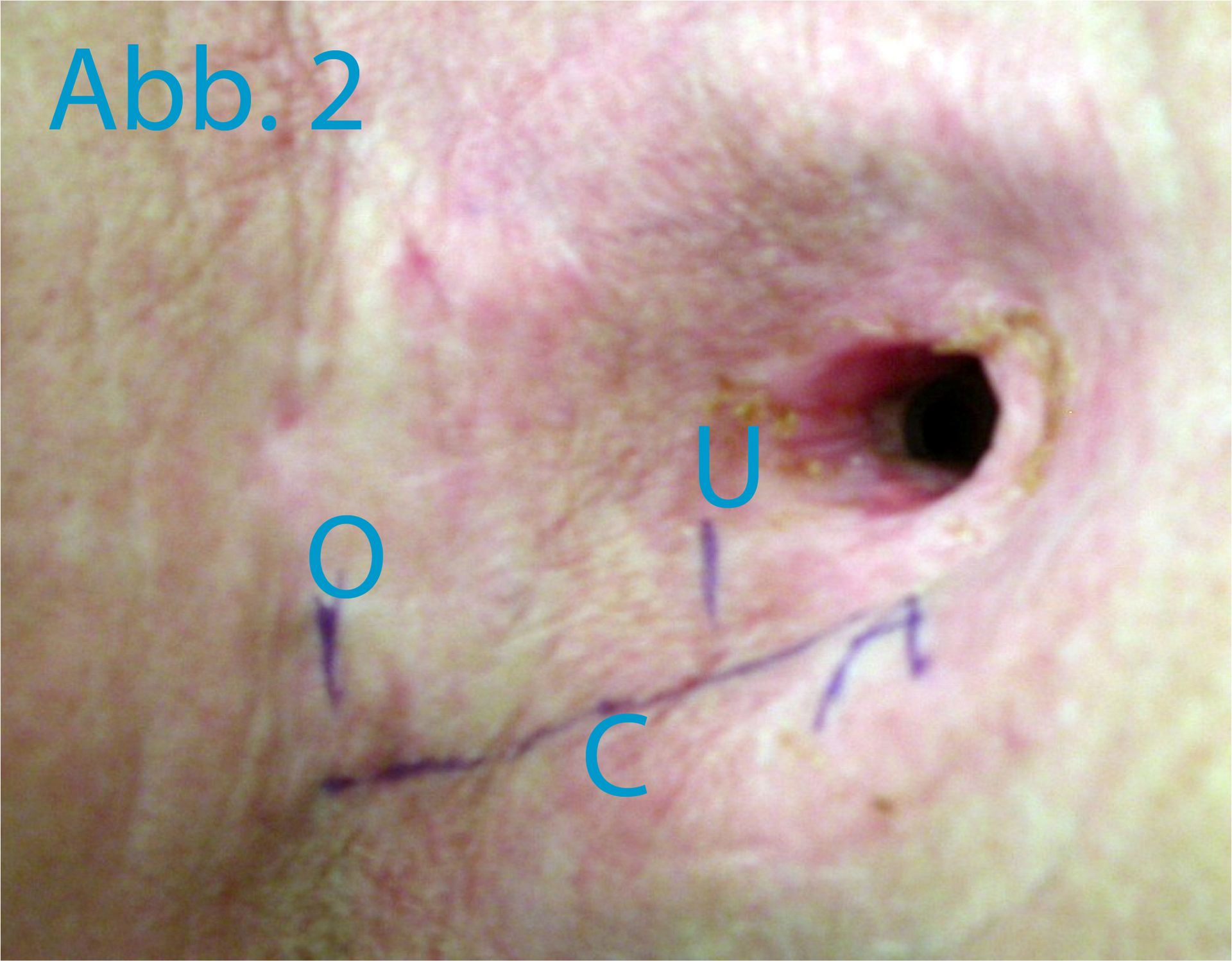

In order to display the spastic pharyngeal segment precisely (the “spastic pharyngeal segment” is in fact a circular contractible section of the constrictor pharyngis muscle), video cinematography of the act of swallowing and the attempt to speak is carried out. A swallow of a barium contrasting agent is taken to rule out high-grade pharyngeal stenoses under frontal and lateral fluoroscopy (ill. 1a). The mucous membrane of the pharynx is only colored for x-raying for a few minutes. The attempt at speech is made in side projection. The top edge of the tracheostoma is marked with an x-ray-proof marker (e.g. a paper clip). The patient then closes his tracheostoma manually and tries to say “Aaah” with some force. The fluoroscopy is carried out while this attempt is being made. Typically, there will be an image on which the spastic pharyngeal segment is visible, as shown in ill. 1b. The distance between the top edge of the tracheostoma (marker) and the spastic pharyngeal segment can now be measured and marked on the patient, as shown in ill. 2.

Test injection with Lidocaine

A test injection with Lidocaine now follows in order to confirm pharyngeal spasm as the reason for the patient’s inability to speak. 5 to 10 ml Lidocaine 1% are infiltrated 0.5 – 1 cm deep into one side of the sketched segment (see ill. 2); bilateral injection may cause problems swallowing. If the patient is able to speak after a few minutes, then pharyngeal spasm is confirmed. An EMG-controlled injection of Botulinum toxin to treat the pharyngeal spasm will most probably be successful.

Therapy

If pharyngeal spasm is the proven cause of the inability to speak following insertion of a voice prosthesis, then there are two treatment options: secondary myotomy of the constrictor pharyngis muscle or EMG-controlled injection of Botulinum Toxin A.

Secondary, surgical myotomy of the constrictor pharyngis muscle is a difficult and complicated procedure, since the caroti artery is often moved well over to medial, scarring makes it difficult to prepare the pharynx, and healing is often impaired by radiotherapy. We recommend the EMG-controlled injection of Botulinum Toxin A instead of secondary surgical myotomy.

EMG-controlled Botulinum Toxin A injection

Botulinum toxin prevents nerve cells from transmitting stimulation to the muscle, as the result of which the muscle will not contract provided an adequate dose is given. The muscles usually remain paralyzed for several weeks. For the treatment of pharyngeal spasm, the Botulinum Toxin is injected into the constrictor pharyngis muscle. This will paralyze the circular contracting section of the constrictor pharyngis muscle, which will have been presented radiologically and confirmed by a trial injection of Lidocaine. In order to keep the amount of Botulinum Toxin injected as small as possible and still be sure of suppressing the circular contraction of the constrictor pharyngis muscle, the injection must be made into the segment of muscle in question with absolute precision. This is best done under EMG control (EMG = electromyography). A bipolar EMG hypodermic needle is inserted into the pharynx on one side medial of the carotid artery, and the safe position of the needle in the constrictor pharyngis muscle confirmed by EMG. A depot of Botulinum Toxin is then injected. We use 100 MU Botulinum Toxin A, spreading it over 4-5 deposits along the whole length of the circular contracting pharyngeal segment that was ascertained radiologically. The injection of Botulinum Toxin may be painful, and can cause a coughing fit.

The effects of the injection can be expected after 2-7 days. Varying success rates for the Botox injection are given in literature, and it is also highly dependent on the use of EMG. If the injection is carried out as described above, then a success rate of slightly over 90% is to be expected. The effects of the treatment are permanent in around one-third of patients. A further one-third will need a second Botox injection. All others will require repeated Botox injections every 3-6 months.

WARNING: The use of Botulinum Toxin A in this indication is OFF LABEL USE.